Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

A major focus is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). IPF is a lethal lung disease where extensive scarring prevents the uptake of oxygen, leading to respiratory failure. ~35,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the US, and these patients have a median survival of 3 to 4 years. In a subset of patients, the disease shows familial occurrence and several underlying mutations have been identified.

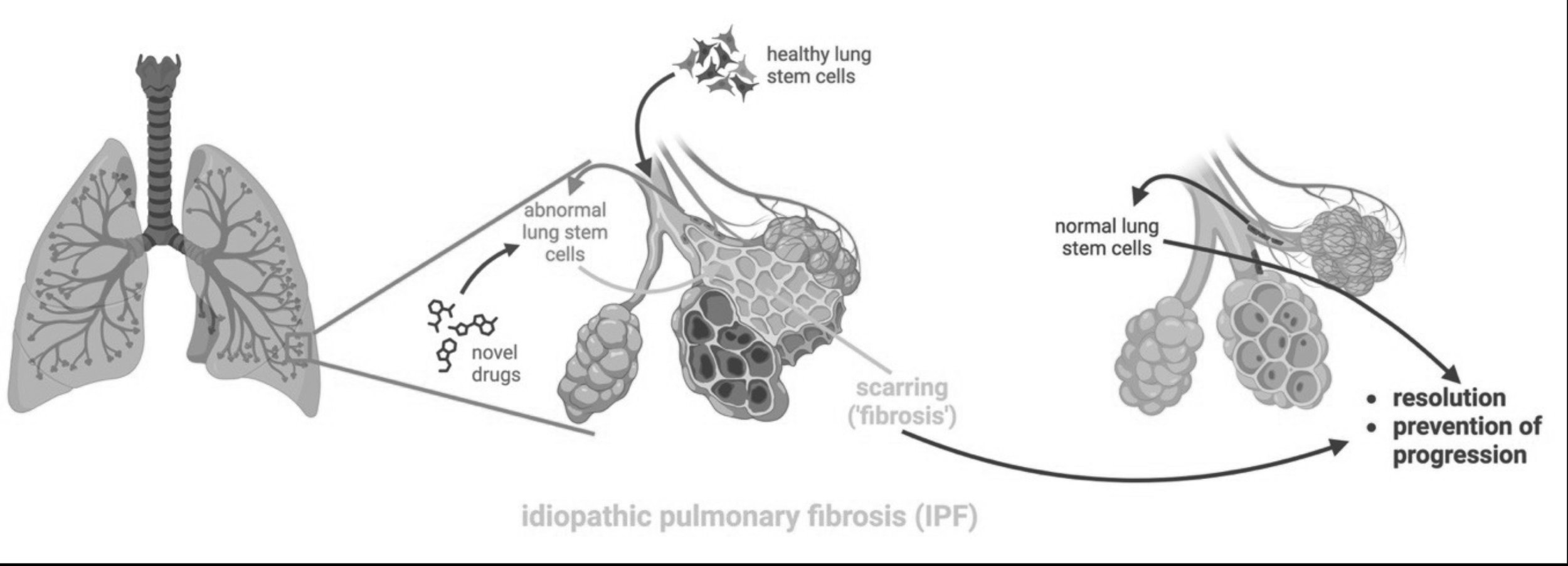

The sole life-saving treatment for IPF is lung transplantation, which remains hampered by a severe shortage of donor organs and immunological complications. Several ‘anti-fibrotic’ (anti-scarring) drugs are available that may slow disease progression to some extent, but are not curative. However, the scar tissue is a result of an abnormal response to injury by the lining of the lung, the epithelium. Any truly curative treatment should therefore correct the abnormal response of the epithelium to injury.

A significant challenge for the field is the fact that mouse models do not faithfully recapitulate IPF and other lung diseases. One reason for the discrepancies between mice and humans with respect to lung disease may be the fact that the distal lung of larger mammals is more complex. The airway tree in larger mammals, including humans, shows more extensive branching and the very distal airway branches contain cells that are absent in mice. Human models are therefore required.

Human lung organoids that recapitulate lung fibrosis in a dish

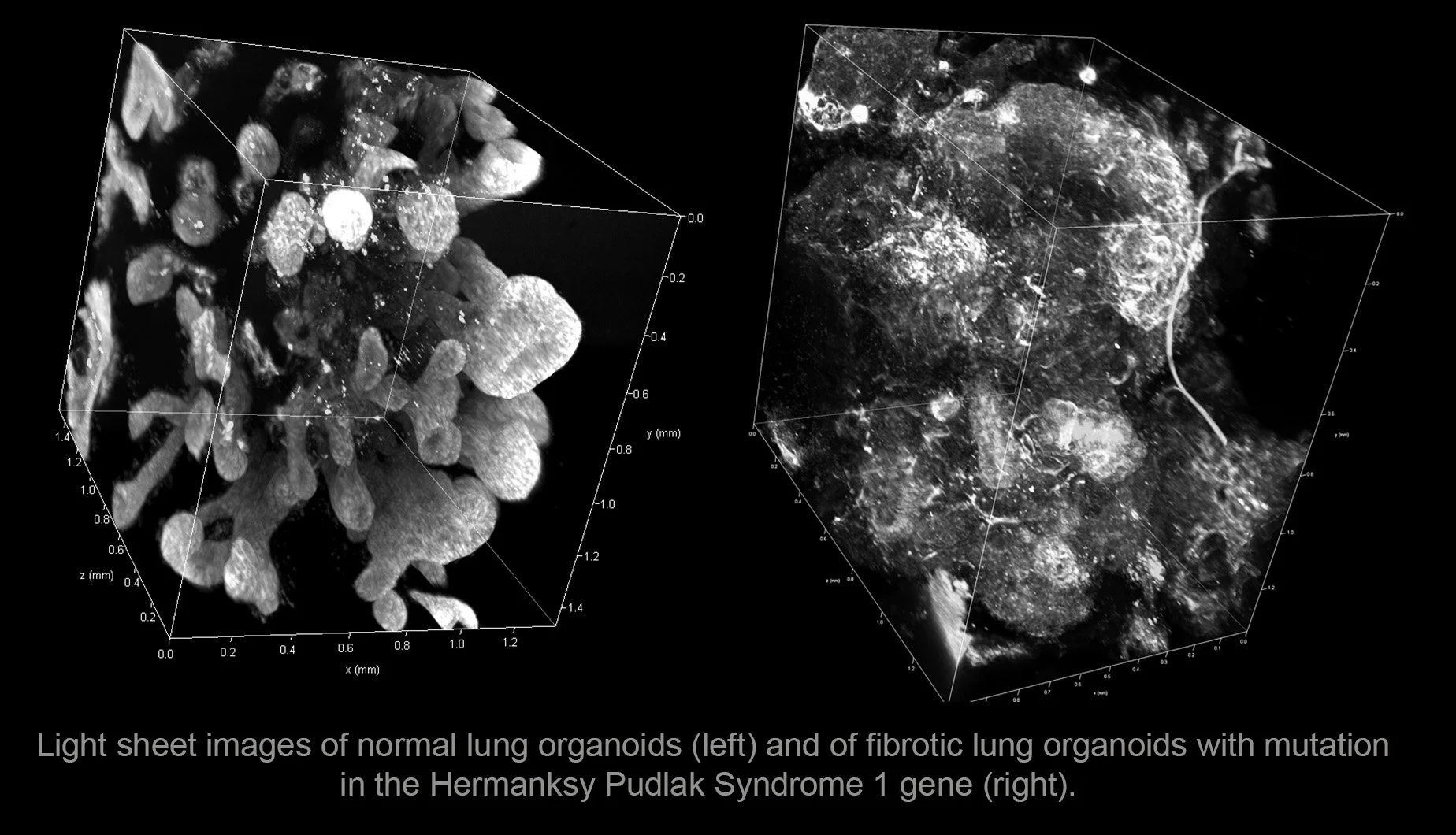

To address these gaps in our understanding, we developed a strategy to generate 3D lung organoids (‘mini-lungs’) from human pluripotent stem cells (Green et al., Nat Biotechnol 2011; Huang et al. Nat Biotechnol 2014; Chen et al. Nat Cell Biol 2017; Matkovic et al., Nat Protoc 2023). We could recapitulate familial forms of the disease (including Hermansky Pudlak Syndrome) in these lung organoids (Chen et al., Nat Cell Biol 2017). This allowed us to identify a factor, interleukin-11, as playing a role in the fibrotic process (Strikoudis et al., Cell Rep 2019). We also used these organoids to model viral infection (Chen et al., Nat Cell Biol 2017;Porrotto et al., MBIO 2019; Ciancanelli et al., Science 2015). https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCe82I_oZrW6goxV8elXe6tw

Courtesy Dr. Remy Schneider, Ph.D., former lab member

Importantly, we could generate from our lung organoids cells corresponding to the very distal airways of human lungs. Using these, we showed that IPF is at least in part a disease of newly identified lung stem cells that sit in these smallest, terminal airways, are unable to repair alveoli and instead generate pro-fibrotic ‘aberrant’ cells (Pezet, Torres et al., Nat Biotechnol 2025). This is important as IPF is currently viewed as a disease primarily of alveolar epithelial cells, not of small airway epithelial cells (Snoeck, Eur Resp J, 2025).

Towards a deeper understanding of and novel therapeutic approaches for IPF and other fibrotic diseases.

Drug discovery: As this work establishes the first in vitro, cell-based model for IPF, we are currently investigating underlying mechanisms and identifying novel drug targets using hypothesis-based approaches and unbiased CRISPR screens.

Cell therapy: Our findings justify efforts at replacing defective lung stem cells with healthy stem cells, thus potentially providing a causal and curative treatment that can be complementary with novel drug treatments. Such approaches may also find application in other distal lung disease, such as acute lung injury. We could generate from lung organoids cells that migrate to damaged areas of the lung, engraft and repair the lung damage in a rat model of lung injury developed by the lab of Dr. Dorrello at Columbia. This strategy is currently used to develop cell therapy approaches for intractable lung diseases. Furthermore, as this represents a partially ‘humanized’ model of lung repair, we are pursuing the study of the basic mechanisms underlying lung regeneration in humans.

Finally, lethal fibrotic disease in many organs, such as kidney and liver, is driven by injury to epithelium. Elucidating the epithelial drivers of fibrosis, as we pursue in the lung, will likely have relevance for a wider array of fibrotic diseases.